| Home | Search | Sitemap | Help | Contact | Sponsors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Home >> Article Database >> Grain Elevators: An Endangered Species |

|

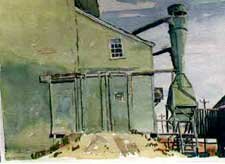

Grain Elevators: An Endangered Species By R.F.M. McInnis

This is the scene all across the prairie of 1998, as more and more elevators are torn down. At a rate of a hundred each year it is happening. Few towns have been left unscathed as the jaws of heavy machinery move in and eat into the aged, dry wood like so many old forest trees. Chewing, chewing, the jaws cut a deep gouge near the elevator's base until at last, with a mighty push, the creaking structure folds in on itself, spewing a massive cloud of dust in the direction of the gaping spectators who line the nearby roads.

This development was brought about as railway companies abandoned more lines in an effort to rationalize their unprofitable prairie branch lines. Nor did it make sense for the elevators every 10 to 14 miles as during the 1930s. Modern trucks allowed the transportation of grain over greater distances. Elevators could now be located 20 or 30 miles apart. Taxes paid to towns and land values were additional considerations for the elevator companies, as well as escalating costs. The inability to expand facilities to 50 or 60 car spotting areas, instead of the current 6 to 20 car availability, was also a factor. Grain companies have elected to go the way of the mega-elevator or inland elevator instead. Unit trains of 100 cars can be loaded at these in 10 to 24 hours, without the need to stop at every country elevator along the way. Such But who would have thought that the demise would come so quickly, within our lifetime? It makes me glad that I was diligent in running around the province recording just about every surviving historical elevator. After 20 years I amassed a large collection of grain elevator photos that represented about 200 Alberta communities as they used to appear. At the same time, I also collected images of towns in Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

Research certainly is one of the main reasons for acquiring such material. In donating two decades' documentation, this collection adds to the museum's existing collection, and ensures that the photos will have a purpose for future generations. The little prairie towns will live forever through the photographs. It gives me a sense of satisfaction knowing that my efforts have not been wasted, and will not be lost like the elevators themselves. Thanks to current technology, the collection will not only be held at the Provincial Museum of Alberta in its photo library, it will be stacked in a computer database under the subject heading "grain elevators" and every print or slide will receive its own catalogue number. Each photo is to be digitized and put on compact disc for research and exhibit purposes.

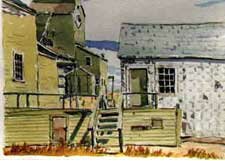

R.F.M. McInnis is an artist who lives and works near Nanton, Alberta. All images reproduced are original works of art produced by the author Mr. McInnis Article reprinted with permission of author and Alberta Museums Review. |

Have you ever noticed a town that's lost all its grain elevators? That's just it. You don't see it. You drive right past without paying much attention. The town is lost forever in a flat wasteland of dizzying prairie space outside your fast-moving car's window, a blur of trees and a few white shapes of bungalow-style houses, if there is anything to notice at all.

Have you ever noticed a town that's lost all its grain elevators? That's just it. You don't see it. You drive right past without paying much attention. The town is lost forever in a flat wasteland of dizzying prairie space outside your fast-moving car's window, a blur of trees and a few white shapes of bungalow-style houses, if there is anything to notice at all. Many of these structures have stood since the turn of the century. Many were built during the wheat boom and co-operative movement of the 1920s. Some towns are lucky enough to have newer ones, built after 1924, or located on railway lines that are still intact. These elevators may survive this most recent round of destruction. But for how long?

Many of these structures have stood since the turn of the century. Many were built during the wheat boom and co-operative movement of the 1920s. Some towns are lucky enough to have newer ones, built after 1924, or located on railway lines that are still intact. These elevators may survive this most recent round of destruction. But for how long? huge concrete structures can hold between 720, 000 and 1.6 million bushels. These big inland elevators are usually located on less expensive lands outside the towns. They seem out of context with the surrounding golden wheat fields. They are not part of their locations, unlike the earlier elevators that seemed to form an aesthetic and harmonious centre for the town. We all knew they would go someday. I knew it when I first arrived on the prairie with my camera more than 20 years ago and started photographing them.

huge concrete structures can hold between 720, 000 and 1.6 million bushels. These big inland elevators are usually located on less expensive lands outside the towns. They seem out of context with the surrounding golden wheat fields. They are not part of their locations, unlike the earlier elevators that seemed to form an aesthetic and harmonious centre for the town. We all knew they would go someday. I knew it when I first arrived on the prairie with my camera more than 20 years ago and started photographing them. When the Provincial Museum of Alberta expressed an interest in this collection as a source of materials for a planned exhibition on grain elevators, it provided the opportunity for me to sort an assess what I had. I quickly decided that I had little need to retain them all, so I offered to donate about 800 to the museum.

When the Provincial Museum of Alberta expressed an interest in this collection as a source of materials for a planned exhibition on grain elevators, it provided the opportunity for me to sort an assess what I had. I quickly decided that I had little need to retain them all, so I offered to donate about 800 to the museum. Who knows, perhaps someday I will be able to go to the Internet, call up my own collection and download 800 images for my files. Then the memory of the grain elevator would truly be preserved.

Who knows, perhaps someday I will be able to go to the Internet, call up my own collection and download 800 images for my files. Then the memory of the grain elevator would truly be preserved.